Seene mein jalan, aankhon main toofan sa kyun hai – iss shehar mai har shakhs pareshaan sa kyun hai?

The bustling Mumbai local, dozens of passengers packed inside the coaches with barely any space for their feet. The train comes to a sudden halt because someone has died on the tracks. Those on the train rue the death not because a man died but because it makes them late for their day. The life lost is not of importance … it is one of many. Every single day. Collateral damage.

It is this scene that captures the essence of Muzzafar Ali’s 1978 classic Gaman.

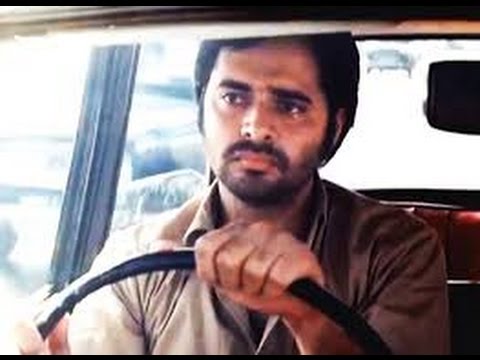

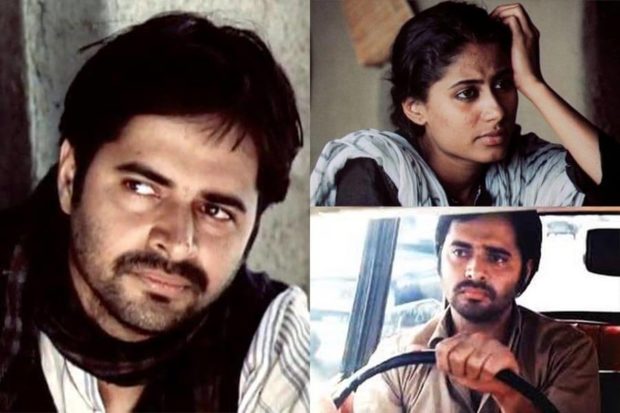

Revolving around the life of taxi driver Ghulam (Farooq Shaikh), the film follows him from Badaun in Uttar Pradesh, which he leaves for Bombay after his land is usurped in search for a better life… And in return for that life barters his identity to the bustling life of the city.

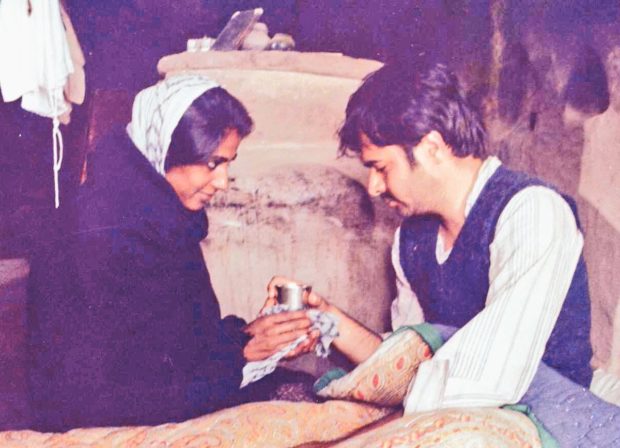

Barters his home and family for a cot in a shanty, barter tilling his land to join the ranks of thousands of taxi drivers. In a search of this life, Ghulam leaves behind his ailing mother and young wife, Khairun (Smita Patil), to face the daily struggles of life in the Maximum City.

I’m no film reviewer. I have no technical knowledge, so I will not delve into the technicalities of the film. But even to my untrained eye, the film is a masterpiece. The film is subtle yet bold. It has a music score that can see one through many a lonely night. I will take this opportunity to tell you what I took back from the film. What stayed with me.

There is no ‘plot’ per se. The film is an observation of the effects that an unforgiving Bombay can have on its migrant workers. The director leaves a lot to one’s own perceptions and interpretations.

The Multiple layers

Through Gaman’s multiple layers, we are shown the glaring inequalities in Bombay. One of the main characters says early on something along the lines of: ‘Everything looks good from the outside, the reality is very different.’ This seems to be a running theme in the film.

The film’s beauty lies in its juxtapositions. Even as the skyscrapers mock the slums, each of Ghulam’s passengers shows the inequalities he faces on a daily basis. A Parsi gentleman talking about the cultural degeneration of the city, indirectly blaming the ‘outsiders’ for doing so.

A rich businessman sitting in the backseat talking about how money is of no consequence in his conquest for an escort – all while Ghulam frets over sending money back home for his old mother’s broken back. Ghulam staring at a mannequin in a shop window as he writes back home that all his money was spent on his taxi driver’s uniform.

The subtlety of the juxtapositions both awe and unsettle you. In one particularly gut-wrenching scene, Ghulam waits for one of his passengers in the searing heat to pay him his 3 rupay 15 paise as she ‘forgets’ he’s waiting. Her penance is a 35 paise tip.

There are moments from the film that stay with you long after the film is over. The death of a taxi driver is conveyed by announcing the number of his car – another painful reminder that this city does not care for its workers’ identity. An apparent ‘madman’ tries to set the sea on fire – a task as impossible as carving a name for oneself in the hustle and bustle of Bombay.

The music score by Jaidev, who won the National Film Award for Best Music Direction in 1979 for his work, is transformative. The silhouette of Khairun bent over her mother-in-law fingering a letter by her husband, as ‘Aap ki Yaad Aati Rahi’ plays in the background, makes you empathise with the young woman who has been separated from her beloved and is all alone.

‘Seene Mein Jalan’, playing behind a montage of visuals from Bombay, in both its glory and its chaos is a lyrical masterpiece. Every word leaves you with an ache in your heart but a smile on your face. The opening shots of the film are set to the tune of ‘Aa Jaa Saawariya’ which sets the perfect tone for the larger message of the film.

The migrants’ crisis

It’s a film that finds itself relevant even today, perhaps even more so. The migrant crisis and how it is being dealt with during the coronavirus lockdown is exactly what Ali had predicted with his film. No one is sparing anyone a second thought in the big cities. Migrant workers have become little more than statistics for many.

Growing up in an upper-middle-class family, I myself have heard people say, ‘If the choice is between us and them, it’s simple. They have to suffer, that’s just the collateral damage in a crisis like this.’ That terrible phrase again: collateral damage.

As lakhs of migrant workers struggle today to find their footing a situation that has chewed them up and spit them out, I know I’ll be thinking of Ghulam and the last montage of the film. Khairun waiting for him by the door as he sees another train pass by him. But refuses to get on it, chasing that elusive ‘better life’.

I began this piece with a quote from the song. I’ll leave with the one line that impacted me the most.

Kya koi nayi baat nazar aati hai hummein, Aayina humein dekh ke hairaan sa kyun hai?

By Nishtha Shanti

And you make a lot of sense as a writer and you know what? You wouldn’t if you did not have a heart that beats in its right place. Gaman is now in my watchlist because I read this piece.

Very evocative, Nishtha!, am going to see the film again. Keep writing!